In 1977 the University of Melbourne Library acquired a large collection of Russian material from a private collector.[1] Included among the boxes of books, pamphlets and serials was a collection of satirical journals consisting of 53 titles in 149 issues dating to the first Russian Revolution (1905–1907).

|

| Voron (The Raven), no. 1, [1905?] |

The revolution was sparked on 22 January [9 January Old Style] 1905, when members of the Russian military and paramilitary opened fire on crowds of people gathering throughout St Petersburg and converging on the Winter Palace to petition Tsar Nicholas II for better working conditions and civil rights. Hundreds of men, women and children were killed or wounded. The brutal action led to national strikes, peasant uprisings, and attacks on figures of authority by revolutionaries and anarchists.

In an attempt to stem the upheaval, the tsar enacted a series of political and social reforms in the October Manifesto (1905), which led to the creation of the Duma and included a loosening of restrictions on the press and freedom of expression. By late November/ early December many revolutionary satirical journals began to appear on the streets of Moscow, St. Petersburg, and eventually in other major cities across the empire.[2]

|

| Vampir (The Vampire), no. 2, 1906 |

|

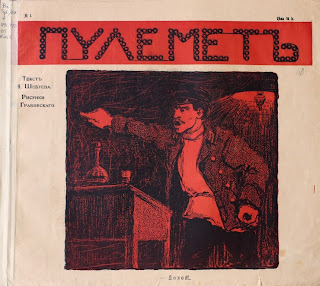

| Pulemet (The Machine Gun), no. 1, [13 December] 1905 |

Most of these periodicals had very short runs. Some of them appeared in only one issue before the authorities intervened to prevent further publication. Various editors attempted to circumvent the censors by changing a publication’s title. Burelom (Storm-Wood), for example, was shutdown in 1905 after four issues, but resurfaced as Burya (The Storm) early the following year. Burya reached a fourth issue, too, before being closed. It was later resurrected as the aptly titled Bureval (Storm Debris).[3]

|

| Burelom (Storm-Wood), Christmas issue, 25 December 1905 |

In addition to journals, propagandist postcards were also produced. Some of the 39 examples in the collection were printed by chromolithography. Others were hand drawn and then reproduced either by hand or mimeographed in outline and then hand-coloured.

|

| Russian Satirical Postcards, 1905 Revolution, nos. 29-34 |

According to Tobie Mathew, who has been collecting and researching these cards for a number of years:

'Leftist postcards were published by both revolutionary activists and legally registered publishers, many of whom were motivated as much by commerce as they were ideology. Some were used and displayed with subversive aims in mind, but most were bought for private consumption; these were objects that in reflecting political beliefs also served to amuse and divert.'

Regarding their rarity, Mathew commented that such cards:

'Don't come onto the market very often … The postcards were avidly collected at the time but being more ephemeral objects they are far less likely to have survived the various upheavals’.

Collections of Russian satirical journals are found in institutions across the northern hemisphere. My suspicion, however, is that the journals (and especially the postcards) held by Special Collections is the only one of its kind in Australia, making it a unique resource ripe for research by local and regional scholars and students.

Readers can view the often striking (and sometimes lurid) journal cover illustrations and postcards on the University of Melbourne Special Collections Flickr page:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/uomspecialcollections/sets

[My sincere thanks to Simon Beattie and Tobie Mathew for offering their expertise so freely]

References

[1] See Leena Siegelbaum’s ‘The O’Flaherty Collection’ published in Australian Academic and Research Libraries (Sept. 1980): 189–194.

[2] The first journal was Zritel (Spectator), which appeared in June 1905. The University of Southern California's 'Russian Satirical Journals' website notes journals were published in Armenian, Estonian, Georgian, Polish, Ukrainian and Yiddish.

[3] David King and Cathy Porter. Blood & Laughter: Caricatures from the 1905 Revolution (London: Jonathan Cape, 1983), 42.